All the camps have weekly meetings. Three service teams divide responsibilities for eight Safe Spot Communities (11-18 Huts) and six micro-sites (1 – 6 Huts). The team Facilitator leads the community meetings and is the primary link between the camps and CSS headquarters. Each team also has a Service Navigator, who helps community members with access to services and attends meetings every few weeks, and two Support Workers, who spend time in the camps to build trusting relationships with clients.

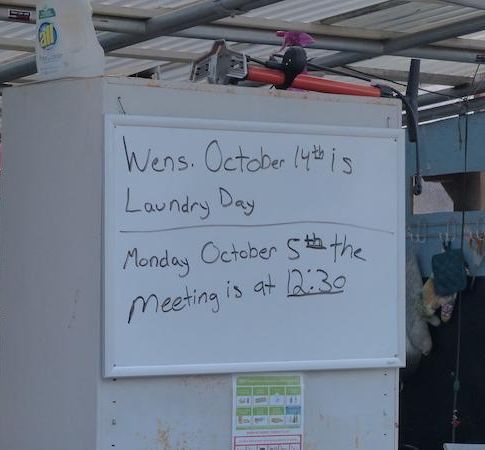

Meetings usually begin with check-ins, with each person describing how things are going for them, with the facilitator often asking for some positive or reflective observations like “say something nice about somebody else in this room” or “tell us what you like or don’t like about fall.” Then the Facilitator will run through a list of announcements about services from CSS (“laundry service is temporarily suspended until a new person is hired; anybody interested should apply at the office”); about upcoming events at the camp (“work party next week; be there or let me know why you can’t make it”); about the status of maintenance issues (“front screens for the Huts are in the works and should be here soon”).

If a Service Navigator is present, they will provide updates on service-related programs, such as deadlines for applying for housing, and reminding members about scheduling appointments with them to keep track of their pursuit of services. And there is usually some discussion of recurring challenges, often starting with what Facilitator Laura Diamond describes as “dishues”—the perennial community disputes about who is or is not doing dishes, but also including other issues like pets and keeping gates locked.

Meetings serve a vital role of “bi-directional” communication between camp members and CSS staff, says Barbara Coleman who has been in the Empire Safe Spot Community since the beginning of 2022. It’s an opportunity for “everyone to have a voice in the needs of the community. . . It also gives participants an opportunity to get to know each other a little better.”

Meetings are “absolutely essential,” says Justin Nichols, who has been in the CSS program about a year and is now in the Expressway camp, after previously living in the Westmoreland and Roosevelt camps. “People need to communicate. You can’t completely mind your own business. Everyone’s business is to some degree everyone’s business.”

Meetings can be calm and orderly, or free-wheeling and raucous, supportive or contentious, often filled with lots of laughter and sometimes tense. They vary from camp to camp and week to week. “Different meetings have different vibes,” Laura says.

“Sometimes we will all be out here and everyone’s laughing and carrying on, and then two hours later, bam! I don’t know what it is,” says Connie Roberts, who has been in the Westmoreland camp for about 10 months. “But when you’ve got this many people and we’re all different, we all have our own weird little shit that we’re going through. So you’ve got to kind of take it with a grain of salt in a sense.”

When Facilitator Orion Martin asked people at an Expressway Camp meeting to say something nice about somebody else, one woman who’d been in the camp a year, said “Everybody does a good job living in a community. It’s getting better. It’s getting way better.”

Yet later in the same meeting, a discussion about a frequently missing gate lock led to talk about a specific individual, who was not present, who was suspected of taking the lock and was otherwise creating problems in the camp. All those who spoke up told of uncomfortable encounters and a consensus seemed to develop that people did not want him in the camp any longer. Orion stressed that that man was suffering, going through a mental health crisis, and that he was addressing his situation by trying to relocate him. Community members expressed sympathy for that individual but, as one man put it, “if it wasn’t for the aggressiveness,” he would be willing to find ways to accommodate him.

“The meetings are pretty good for taking the temperature of the community,” says Morgan from the Westmoreland camp, “If things are really out of control, the meetings are probably going to blow up into a giant brawl. But if things are somewhat stable, then the meetings are going to be somewhat stable.”

Meetings are “really important for our community because there’s not a lot of interaction other than in meetings,” says Jesse Descavich, who’s been at the Empire Safe Spot Community for eight months. “It’s a good space where we all get together to figure out if there is anything going on. It takes work to get it out in a pro-social way, so that’s community building for us. As we do that, it gets better every time.”

Laura, the Facilitator at Empire since its opening about a year ago, says conflicts in meetings can be difficult. But she welcomes conflict as an inevitable ingredient of any community. She promotes “sharing power, sharing space” among all members of a Safe Spot Community, to try to help them feel safe to engage in a conflict resolution process. And when breakthroughs do happen, she says, it really does strengthen the bonds of the community.

But it’s not easy.

“This stuff comes up in the meeting, but everybody just sits here” says Connie from Westmoreland, “The Facilitator will ask, ‘Did you see that? Does anybody have a beef with something?’ We don’t say anything in our meetings because one person will get up and walk out and then you’re not solving anything anyway, because they feel like they’re being attacked.”

Barbara from the Empire Safe Spot says, “Meetings can be a starting point for critical conversations.” Simple misunderstandings can be resolved but people are sometimes reluctant to discuss deeper issues in open meetings because they don’t always feel safe with all the other members of the community. “Laura is pretty good about setting boundaries for scenarios where it’s more appropriate to take it offline and discuss it more privately in a calmer setting with fewer distractions.”

Meetings “give people space to actually talk, where if they didn’t have a platform, it would kind of fester,” Justin from Expressway says. “I don’t necessarily see them solve [problems], but it’s not good to just keep your resentments inside. It’s important for people to say what’s going on.”

“As long as you’re talking to each other, that’s good,” says Morgan from Westmoreland.

Orion has recently changed his approach to his facilitation role. He has changed the times of the meetings at the three camps he works with from mornings to noon, each camp on a different day. On meeting days, he tries to spend as much time as possible in the camp.

“One of the reasons I’m in the community more now is that I want to get to know these people better outside of meetings, so I can help serve them better,” he says.

His increased presence has been accompanied by a greater emphasis on enforcing rules in the camp. When he started the new meeting schedule, he placed a white board with the rules listed in the community buildings where the meetings take place and started the meeting by bringing attention to it. He said he would be enforcing these rules with “write-ups.” Three write-ups lead to eviction.

One of the longstanding rules is that attendance at community meetings is mandatory. Absences are excused if people have jobs or appointments for housing or medical issues or other such obligations. But attendance can be spotty.

A week after Orion’s warning about increased enforcement, about half of the members at one of his camps didn’t show up for the weekly meeting, so he went Hut to Hut writing up the people who hadn’t shown up.

“I think about half of the community is a little upset,” he says. “But I’m going to use it as a tool and we’ll bring it back around next week.” He hopes his presence in the camp and more consistent application of rules will encourage members to participate willingly in the meetings.

Orion, like other Facilitators, would prefer to “see more of a positive reinforcement model rather than this negative stuff, but this is what we’ve got right now and I’m sure it will change over time.”

Orion’s shift to spending more time in the camps is part of a general effort of the CSS service team to be more of a presence, but the specifics for each team member are still being developed. Laura supports the general idea and already makes a point of connecting with the individuals in her camps, but, she says, sometimes there can be too much staff presence, intruding on the privacy of the members. Laura’s approach to meeting attendance is to “make sure everybody shows up sometimes.”

Westmoreland community member Morgan sees a lot of these issues about meetings and rules as a result of trying to find a balance between community and freedom.

“We’re given a lot of freedom here. Freedom is important; community is important. We have freedom and we have community.

“We shouldn’t have to have a baby sitter. We shouldn’t have to have video cameras. We shouldn’t have to have all these rules. But we do have to. It’s necessary.

“It’s trying to find a balance between treating people like human beings and at the same time, trying to impress upon them that they’re adults and they’re allowed to make choices. And if they make wrong choices, nothing you can do for them. You can make the wrong choices and sometimes you’re just going to fall flat on your face.”

Several community members mentioned that they had noticed recent changes that had improved the connection between CSS staff and the people in the camps “like implementing rules and infrastructure improvement and accountability,” says Jesse, “paying attention to what the campers’ needs are. We’ve been struggling here for a long time. . . . They’re allowing the staff to spend more hours with us to help us heal.”