It’s worked for Rose, 25, who lived in CSS Safe Spots with her husband Jeremy for most of two years after four years living in fields—to some extent. For the last three Christmas seasons, she’s worked as a Santa’s helper at Valley River, a job that averages about 30 hours a week from early November through the holiday. That position also led to a job assisting the Easter Bunny at the same mall. But it took a lot of persistence for Rose to land those temporary jobs, and full-time steady work remains an elusive goal. Finding any kind of work, which can be an important step on a path out of homelessness, is tough for anybody without an address and all the stigmas attached to that condition.

“Once they find out that you’re homeless, it’s ‘you can leave the establishment now,’” says Shawn Cooper, a 40-year old who moved into the Veterans Safe Spot in January. “They don’t even want you to come in the door.”

Cooper has been homeless off and on since 2005 when, after watching his best friend kill himself and finding out his wife had been cheating on him, he attempted suicide and subsequently received a less-than-honorable discharge from the Navy, where he served for six years, the last four as an operations specialist. He spent seven years “in the woods” in Missouri. In 2013, his daughter Autumn Nicole (one of his five children) came back into his life by inviting him to her wedding. That experience “woke me up,” he says. “It gave me a purpose again.” Around the same time, a friend in Oregon suggested he come out here and try to get some help rebuilding his life.

Since then, Shawn has been in and out of housing, largely because of an on-and-off relationship with a woman. The swings in that relationship have followed his employment status: “Each time I would lose a job, each time we would fall on financial hardship, she’d bolt,” he says. “When I get another job and I start getting stable again, she wants me back and I’ll give it another try, but it falls through my fingers and she up and leaves and then I end up back out homeless.”

His situation is complicated because of his less-than-honorable discharge from the military, which is another obstacle when seeking stable employment and prevents him from getting assistance from the Veteran’s Administration. He has had help from local veterans’ services, including support in appealing his discharge status, which was also backed by Representative Peter DeFazio. An earlier appeal was denied, but he has recently launched a new appeal.

He got laid off from his last job just before last Christmas and ended up living in a tent in a wooded area in Springfield through the ice storms and freezing weather (“I swear to God, I almost died out there,” he says). One day, he knocked on the door of the CSS office by mistake when he had a meeting scheduled with St. Vincent DePaul’s Support Service for Veteran Families at the church across the street. A few days later, he returned to his camp to find everything gone. He went back to CSS “to see if maybe they could figure something out, somewhere to lead me. They could tell I was shook. By the end of the day, they had me in [the Vet’s Camp]. I was very blessed.”

Shawn continues to actively look for work and offers a variation of Rose’s advice to homeless people looking for work: “Be as proactive about your situation as possible, don’t expect somebody to do the work for you. If you want to change, that’s the only way it’s going to happen.”

And despite his string of setbacks, he remains optimistic: “I’m always going to have hope because I refuse to give up. I know that I’ve got the drive and the ambition, I just need the chance.”

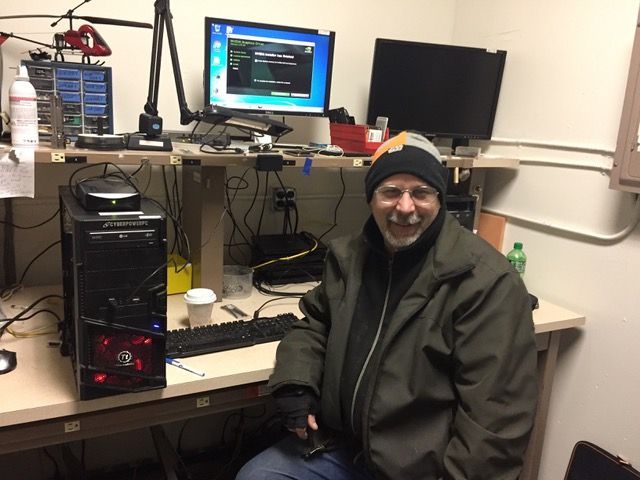

George Sisney got the chance he needed when he was still camping by the Willamette River, waiting to get into the Chambers Safe Spot. He had met with Erik and Fay de Buhr in early summer of 2015 to see about getting into a camp. In the course of that conversation, he heard about NextStep Recycling, and he knew the work they did with electronics recycling and reuse was “right up my alley.” He was determined to get a job there, and when he found out they welcomed volunteers, he jumped at that chance.

Through all these changes, he showed up at NextStep. “When I found out I could volunteer, that’s what I did—six days a week almost nine hours a day.” He worked on many aspects of the process at NextStep, which receives donated electronics and either recycles them or repairs them for reuse, through sale in a retail store. Part of its mission is also to offer “job and social training to community members.” George dismantled computers, worked in the audio-video area, evaluated computers, built computers from recycled components —and then became assistant to the lead technician in the repair shop. In August last year, after a year of volunteering, he was hired to take over as the lead technician—full-time and paid.

George adds stubborn to Rose’s annoying as traits that homeless people sometimes need to get employed. He found the job he wanted and was willing to work for free and to live without stable housing to get it. “I wasn’t going to go look for a job that was demeaning or something I didn’t like,” he says. “I’m stubborn that way. There’s a difference between voluntary houselessness and involuntary. It started out as involuntary but because I wanted this job so bad, it became voluntary.”

He loves his job. “I love working with computers,” he says. “I love working with technology. I get all the great toys to play with. I love fixing things and learning. I’m always, always, always learning something new all the time and I’m challenged.”

But it took him almost five months after he got full-time work to find housing he could afford. He moved into a studio apartment in January. “The rental market in Eugene is horrid,” he says. “They’re catering to nothing but the university. All the housing is sucked up by them. Now I understand why there are so many people out there who are houseless.”

His advice to other people who are homeless, and especially those who are given a chance in the Safe Spots, is to take advantages of opportunities when you get them. He says he has seen too many examples of people who get comfortable in a camp and it becomes “couch potato time.”

“If you want something like what I was going after,” he says, “you’ve got to work for it, you’ve got to be focused on it.” But how many people—homeless or not—can or would spend a year working for no pay?

Rose Jordan has done some of that. She volunteered in the Community Supported Shelters office for seven months in 2014-15, which she says allowed her to contribute to the organization that was helping her and to get training for work as a receptionist. It also kept her from being bored, one of the things, she finds most annoying. Currently, she is working on a trade basis at the Broom Closet, an alternative collective clothing store—a “punk rock store” in Rose’s description. She gets $11.25 an hour in trade value and has been told she will get a paying job when the store starts hiring.

Even a person as persistent and positive as Rose, though, has run into a lot of hostility in her dogged pursuit of a job. “Oh my gosh, nobody wanted to take me—sorry to say this—because I was homeless, and they thought, “‘Oh, hey, every homeless person is the same.’”

She has put in applications at Fred Meyers, Safeway, Dollar Tree, Target, and Bed Bath & Beyond—in some cases multiple times. But she often doesn’t even hear back. “It’s really hard trying to find even a minimum wage job that would give you a chance,” she says. “People want high-end energy but when you go in and show them how you are and who you are—they go, ‘oh, we want you’ but when you do the initial interview and they find out your homeless, it’s like, ‘oh, I’m sorry we don’t want you.’”

She was fortunate that the woman hiring for the Santa’s assistant job could see her for the qualities she displays—high-energy, integrity, honesty (to the point that she couldn’t not tell people she was homeless), friendliness—“not just for my homelessness,” she says. And once given that chance, she performed well enough that she’s been welcomed back for two additional years, with raises above the initial minimum wage.

But that is part-time seasonal work.

So, bolstered by an inner joy and her Christian faith, she keeps on trying. She and Jeremy moved into an apartment in the building next to the CSS office in June with help from a Shelter Care program. In addition to enjoying sleeping in a bed and waking up warm in the mornings, one of the best things about being in regular housing is that she has an address to put on the applications she keeps filling out and turning in: “Yahoo!, I can actually put that down,” she says. “It makes me happy and I have that awesome possum feeling about it. It’s just grand.”

“The experience while I was in camp is what gave me the self-motivation and the self-persistence—the annoyingness—to be actually willing to be out there and find a job. And now, having an actual apartment and a roof over my head is basically the icing, cherries, whip cream, sprinkles on top of the cake.”