Missing Rungs: The steep challenges of climbing out of homelessness

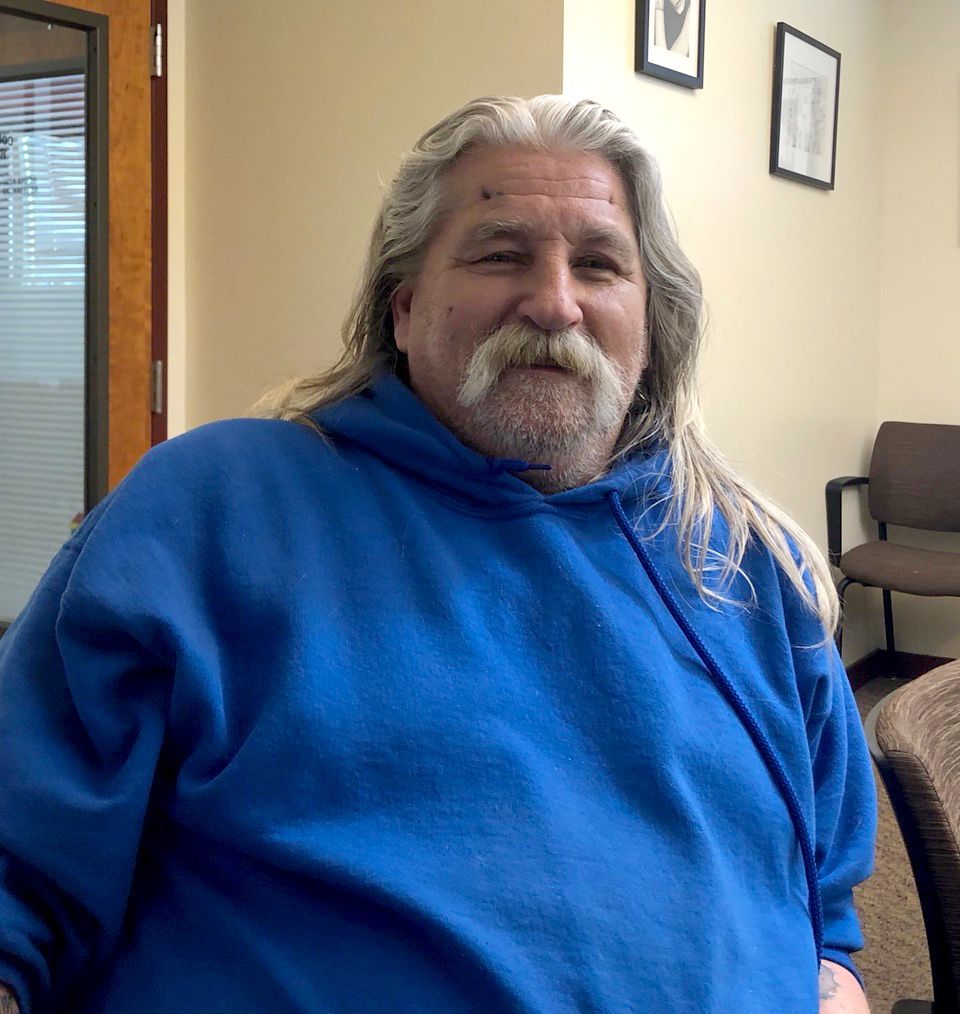

But Charles spent 25 years in prison for a felony he claims was a set-up by a vengeful, corrupt prosecuting attorney in Idaho, and Cynthia is Samoan, with a golden tone to her skin. They both have physical disabilities. For all their efforts, no one has offered them an apartment.

“People look at you crossways when they find out you served time in prison. They’re afraid,” Charles says. “People have a hard time with the color of my skin and my disability,” Cynthia says. Because of their disabilities—Cynthia had a brain injury as a child that did lasting damage and a more recent stroke that renders her left hand unusable, and Charles has been in a wheelchair for twenty-eight years because of deteriorating disk and bone disease and spina bifida—they need to live on a lower floor with accessibility.

In a housing market like Lane County’s, where strong demand and a significant shortage of affordable housing create steep barriers, those personal factors make each step toward a home an even taller order.

Tiffany has two felonies on her record, the most recent in 2016 when she thought she was in danger and “freaked out” when authorities tried to force her to leave a hospital where she had sought refuge. She got three-years’ probation, which she has served successfully and will complete at the end of October this year.

She was at the Mission before first moving to the Roosevelt camp in December 2017. When she had reached the ten-month limit there without finding housing, she moved into a Conestoga Hut at Messiah Lutheran Church in Santa Clara. But after a couple of months there, she says, she got lonely and a new spot opened up at Roosevelt, so she moved back earlier this year.

“I’ve been looking for housing the whole time since I was at the Mission. I was seeing my counselor there and filling out any paperwork or forms she had.” Since then, with help from CSS, she has been working with St. Vincent de Paul and is planning to see if she can get help from Catholic Community Services. “I’m more than happy to fill out any form possible that will help me achieve something higher than what I’m doing right now,” she says

But when her hopes have been raised, her past felonies have knocked her down. “At one place they said, ‘You’re a felon and we don’t really want felons.’” Another time, she got a letter saying she wasn’t the kind of person they wanted in their facility. “And they said I lied about it, but I didn’t lie about it. I just put down the two worst things.” She says she didn’t realize the expectation was that she would list her entire history.

“They always talk about the felonies, so I thought I could speak to them and say, ‘Yes, I had two felonies and here’s what happened with them.’” But she didn’t get that chance.

Tiffany finds some hope in women friends from the camp who have successfully found housing. But two examples she mentions both had help from family members providing a boost into more traditional and stable housing situations. Once in that sort of housing, people have a better shot at establishing the history necessary to open up other housing opportunities.

“I don’t know that many people,” Tiffany says.

Every person in the CSS program is assigned an action plan advisor who meets regularly with them and helps them move from wherever they are when they enter the program toward their personal goals, including finding conventional housing.

Marie Laura Roehrich works with Tiffany and Charles and Cynthia. She says felonies are difficult to overcome, but there are legal support agencies who will help people expunge felonies at reduced rates. CSS has a general assistance fund available to help clients with expenses involved in cleaning up their records. But there are many stipulations as to who is eligible to have felonies expunged and no one in the CSS program has yet been able to take advantage of that. For example, even after Tiffany completes her three-year probation, she may still be ineligible because of her earlier felony. And Charles’ felony can never be expunged because it involved a sex offense. That also disqualifies him from Homes for Good, Lane County’s low-income housing agency, which will, under certain conditions, accept people with felonies on their records.

Other agencies, such as St. Vincent de Paul and Cornerstone Community Housing, are also open to people with histories that property management companies reject reflexively. But waiting lists are long and opportunities are limited.

Independent landlords could have more flexibility than management companies, if they gave individual applicants a chance to explain their histories and where they are now.

“People come from all kinds of backgrounds and have had to face various challenges,” Marie Laura says. “And even if someone has something on their history, that doesn’t mean that they’re going to repeat it. I think it’s important for people to look beyond the stigmas that society associates with certain choices people have made, to give people the benefit of the doubt that they’ve learned from their experiences.”

“These are real good, good people who’ve just faced a lot of challenges in their lifespans,” she says.

CSS action plan advisors help clients determine what lists they need to get on, to complete all the necessary paperwork, and to get to appointments. They are a part of the compassionate CSS community that also includes the other residents of the Safe Spots and other CSS staffers.

“It’s really helpful for all of them to be in a safe, secure space that creates a stabilized environment,” Marie Laura says. “It makes a difference for them to be in that supportive community so they can put more energy towards this complicated system that just has lots of barriers.”

Tiffany is grateful for the time she’s been in the CSS Roosevelt camp. “I really like this camp. It’s like a family here. I don’t have any family. It’s just nice to have these people that I’ve gotten to know and who make me feel better. I love these people. And then we’ve got the whole other deal over at the [CSS] office. Everybody at the office, they’re just wonderful, wonderful people.”

But she really hopes to move on sometime soon. “That’s what I’m concerned with, because I’m doing this probation and not getting in any trouble and just following whatever I’m supposed to do, minding my Ps and Qs and crossing my Ts and whatever. I’m looking forward to getting off probation, but even then I may not have a place to live.”

She’d just like a chance to explain herself to the person on the other side of her housing application: “I’m fifty years old and I’ve made some mistakes, but I really, really would like to live in your establishment. I understand I have a couple of felonies, one from a long time ago, the other more recent. I want to get my felonies removed, so that’s what I’m working for. But it takes more than just wanting it.”

Rusty is now four years sober and glad to be in the Vets Camp where he finds a camaraderie and respectfulness. “I haven’t ever really look forward to the future. I’ve started looking at that through one of the classes [at Sponsors], Moral Recognition Therapy, and it asks you, ‘What do you want to be doing in five years, ten years, if you had that much time to live, what would you do?’ A lot of it was imagination, but it actually got me to thinking, ‘Yeah, I’m hoping I can save my money up and buy me a modular home or a trailer. A home. So I’ll have my own place. I won’t have to keep moving. That’s what I’ve been doing for years.”